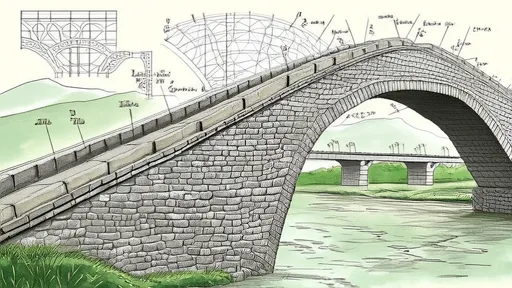

In the realm of structural engineering, the integrity of assemblies often hinges on the performance of their connections. Among these, riveted joints stand as a cornerstone of traditional and modern construction, from the skeletal frames of aircraft to the girders of monumental bridges. The calculation of force distribution in multi-point riveted structures is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical discipline that ensures safety, durability, and efficiency in design. This deep dive explores the nuanced principles and methodologies that govern how loads are shared across an array of rivets, a subject where precision meets practicality.

The fundamental challenge in analyzing a multi-rivet connection lies in moving beyond the oversimplified assumption of equal load sharing. In reality, the distribution of forces is anything but uniform. It is a complex interplay of factors including the geometry of the connection, the stiffness of the joined materials, the precision of the rivet installation, and the nature of the applied load—be it static, dynamic, or subject to fatigue. Engineers must abandon the comfort of simplistic models and embrace a more holistic, analytical approach to predict true behavior under stress.

At the heart of this analysis is the concept of load path redundancy. A single rivet represents a potential point of failure; a cluster of rivets creates a system where the load can find alternative routes should one connection point become compromised or exhibit different stiffness characteristics. This redundancy is the system's greatest strength, but it also introduces complexity. The load does not simply divide by the number of rivets. Instead, rivets closer to the point of load application or those in stiffer regions of the parent material often shoulder a disproportionately higher share of the burden initially.

The material properties of both the rivets and the plates being joined are paramount. A significant mismatch in stiffness—for instance, a very rigid rivet in a relatively flexible plate—can lead to a phenomenon known as secondary bending. This induces prying forces that were not accounted for in initial axial load calculations, placing additional stress on the rivet shank and the hole boundaries. Furthermore, the plasticity of the materials plays a crucial role. As load increases, localized yielding around the most stressed rivets can actually be beneficial. This yielding allows for a redistribution of load to adjacent, less-stressed rivets, effectively creating a more uniform distribution than elastic theory alone would predict. This plastic redistribution is a key safety mechanism in overload scenarios.

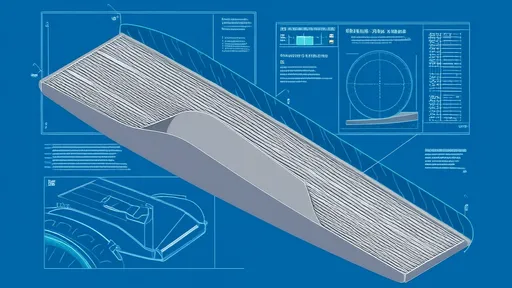

Modern computational power has revolutionized this field. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) has become an indispensable tool, allowing engineers to create highly detailed models that simulate the behavior of a riveted joint under load. These models can account for material nonlinearity, contact interactions between the rivet and the hole, friction, and even the initial stresses induced by the riveting process itself. By running simulations, engineers can visualize stress concentrations, identify potential failure points long before a physical prototype is built, and iteratively optimize the pattern, spacing, and size of rivets to achieve the most efficient and robust force distribution possible.

Beyond computer modeling, physical testing remains a vital, irreplaceable component of validation. Sophisticated methods like strain gauging and photoelasticity provide empirical data on how strains develop across a connection. Tests are conducted to failure to understand the ultimate strength and the failure mode—whether it will be a bearing failure of the plate, shearing of the rivets, or tensile failure of the net section. This empirical data is used to calibrate and validate the FEA models, creating a feedback loop that continuously improves the accuracy of predictive engineering.

The discussion would be incomplete without addressing the critical issue of fatigue. In structures subjected to cyclic loading, such as an aircraft wing, the force distribution calculation is not about a single maximum load but about predicting performance over millions of cycles. Fatigue cracks often initiate at points of highest stress concentration, typically at the edge of a rivet hole. A miscalculation in the distributed load can lead to accelerated fatigue at a specific rivet, precipitating a catastrophic failure. Therefore, fatigue analysis requires an even more refined understanding of the minute stress fluctuations at each connection point throughout the loading cycle.

In conclusion, the calculation of force distribution in multi-point riveted structures is a sophisticated synthesis of material science, mechanical principles, and advanced computational analysis. It moves far beyond simple arithmetic into a domain where understanding the subtle interactions between components is key. The goal is to design a connection that is not just strong, but also intelligent in its ability to redistribute stress, absorb energy, and withstand the test of time and use. As materials evolve and designs become more ambitious, the principles governing these calculations continue to be a fundamental pillar of structural engineering, ensuring that the structures we rely on remain steadfast and secure.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025