In the architectural landscape of modern cities, glass curtain walls have become synonymous with progress and sophistication. These shimmering facades reflect our aspirations toward transparency and connectivity, yet they simultaneously create subtle but profound emotional barriers. The interplay of light through these surfaces—governed by precise optical properties like transmission and reflection ratios—shapes not only the physical environment but also the psychological experiences of those who live and work within these glass-clad structures.

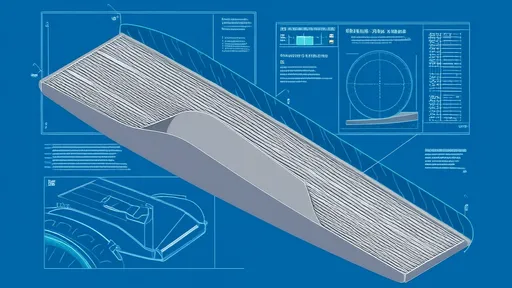

The science behind glass curtain optics is both intricate and fascinating. Transmission ratio refers to the percentage of visible light that passes through the glass, while reflection ratio measures the amount of light bounced back off the surface. Architects and engineers meticulously calculate these values to achieve desired effects: reducing glare, managing solar heat gain, or enhancing privacy. However, these technical decisions carry unintended emotional consequences. High-reflection glass, for instance, might create a mirror-like exterior that dazzles observers but renders the building's interior invisible, fostering a sense of isolation for those inside.

From an urban perspective, glass curtain transform cityscapes into kaleidoscopes of light and movement. By day, they reflect clouds and sunlight; by night, they glow with interior illumination. Yet this very beauty can feel cold and impersonal. Pedestrians walking past highly reflective buildings often see only distorted versions of themselves and their surroundings, rather than glimpses of human activity within. This lack of visual connection undermines the sense of community that traditional architecture with visible windows and active facades provides. The emotional barrier arises not from malice but from the physics of light itself.

Inside these glass environments, the experience is equally complex. Employees working in offices with high-transmission glass may enjoy abundant natural light and panoramic views, which can boost mood and productivity. However, the same transparency can create feelings of exposure and vulnerability, as if one is constantly on display. Conversely, low-transmission or tinted glass might offer privacy but at the cost of a dim, disconnected atmosphere that feels detached from the outside world. The emotional impact hinges on a delicate balance between openness and enclosure—a balance that transmission and reflection ratios directly influence.

Cultural and psychological factors further compound these effects. In some societies, glass symbolizes modernity and openness, making glass curtain aspirational. In others, they might represent corporate impersonality or environmental indifference. The psychological concept of "environmental empathy"—our ability to feel connected to or alienated from our surroundings—is deeply affected by these optical characteristics. When a building's facade reflects more than it reveals, it can feel like a closed book, discouraging emotional engagement.

Architects are increasingly aware of these emotional dynamics. Innovative designs now incorporate fritted glass, dynamic shading systems, or hybrid materials that adjust optical properties based on time of day or occupancy. These solutions aim to reconcile technical efficiency with human emotional needs. For example, glass with patterns or gradients can reduce reflection while maintaining privacy, creating a more inviting exterior without sacrificing energy performance. The goal is to transform emotional barrier into emotional resonance.

The environmental implications cannot be overlooked. Glass curtain with poor optical properties contribute significantly to energy waste through heat loss or excessive cooling needs. This environmental cost adds another layer to the emotional barrier: occupants may feel complicit in or frustrated by unsustainable design. Sustainable innovations—such as double-skin facades or electrochromic glass that adjusts transmission dynamically—address both ecological and emotional concerns by creating more responsive, humane environments.

Looking ahead, the future of glass curtain design lies in smart technologies and biomimicry. Researchers are developing materials that mimic the adaptive qualities of natural systems, like squid skin or butterfly wings, changing reflectivity based on external conditions. Such advancements could lead to buildings that not only optimize light transmission for energy efficiency but also for emotional well-being, perhaps even adjusting transparency to match the mood or needs of occupants. The emotional barrier caused by static optical properties may soon give way to dynamic, empathetic architectures.

In conclusion, the optics of glass curtain—transmission and reflection ratios—are far more than technical specifications. They are powerful determinants of how we feel in and about our built environments. As we continue to clad our cities in glass, we must prioritize not only aesthetic and functional outcomes but also the subtle emotional textures these surfaces create. By marrying scientific precision with psychological insight, we can design glass curtain that connect rather than separate, illuminate rather than dazzle, and inspire rather than intimidate. The true measure of their success will be not in their reflectivity, but in their ability to make us feel at home.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025