In the quiet corners of architectural history, where mathematics meets masonry, there exists a peculiar intersection of form and function that has captivated builders and mathematicians alike for centuries. The geometry of spiral staircases represents one of the most elegant applications of mathematical principles to structural design, with the catenary curve standing as its unsung hero. While most observers admire spiral staircases for their aesthetic appeal or space-saving efficiency, few recognize the sophisticated mathematical underpinnings that give these structures their remarkable stability and grace.

The story begins not with staircases, but with chains. When a uniform chain is suspended freely from two points, it naturally forms what mathematicians call a catenary curve—a word derived from the Latin catena, meaning chain. This curve possesses extraordinary mechanical properties: it represents the ideal shape for a hanging chain supporting only its own weight, distributing tension perfectly along its length. For spiral staircases, this principle translates beautifully to the hanging handrail, which when inverted, provides the optimal structural form for supporting the steps while minimizing material stress.

What makes the catenary so remarkable in staircase design is its relationship with gravitational forces. When architects invert the catenary curve to create the central column or supporting structure of a spiral staircase, they essentially create a compression-only form—the exact opposite of the tension-only hanging chain. This inverted catenary provides unparalleled stability, as each component of the structure handles compressive forces in the most efficient manner possible. The result is a staircase that feels both impossibly delicate and remarkably sturdy, a paradox that has fascinated architects from Gothic times to the present day.

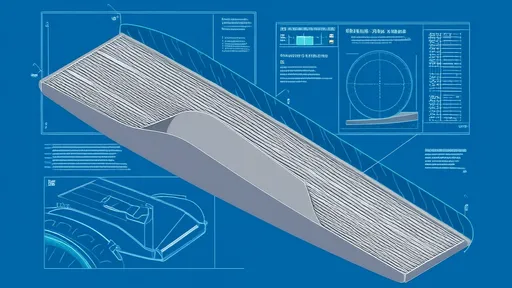

The visualization of catenary equations in staircase design represents a fascinating convergence of abstract mathematics and practical construction. Through parametric equations and modern computational tools, designers can now precisely calculate the optimal curve for any given staircase configuration. The mathematical expression y = a cosh(x/a) – where cosh represents the hyperbolic cosine function – might seem abstract on paper, but when rendered in three dimensions becomes the blueprint for breathtaking architectural features. This translation from equation to edifice demonstrates how ancient mathematical principles continue to inform cutting-edge design.

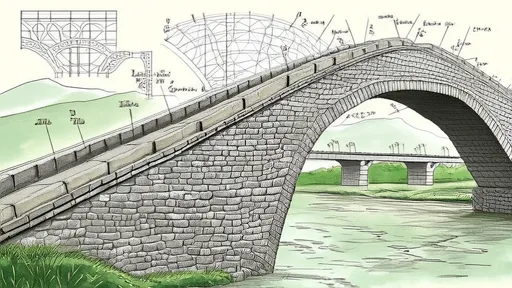

Historical examples of catenary-inspired staircases abound, though their builders often arrived at the forms through intuition rather than explicit mathematical understanding. Medieval masons constructing spiral staircases in castle towers discovered through trial and error that certain curves provided better structural integrity than others. The magnificent staircases of Renaissance palaces, particularly those in Italian villas, often exhibit nearly perfect catenary forms despite their architects lacking formal knowledge of the underlying mathematics. These craftsmen essentially reverse-engineered the mathematics through observational wisdom and accumulated building experience.

The Gothic period witnessed particularly sophisticated applications of catenary principles, though builders of the time would not have expressed their knowledge in mathematical terms. The famous spiral staircases of Chartres Cathedral and other medieval structures demonstrate an intuitive grasp of optimal curvature that would only later be formalized mathematically. The stonemasons' guilds guarded their construction secrets closely, passing down dimensional relationships and proportional systems that effectively encoded mathematical principles without explicit equations. This transmission of practical knowledge represented an alternative form of mathematical understanding—one based on geometry and proportion rather than algebraic formulation.

The formal mathematical understanding of the catenary curve began to emerge during the Scientific Revolution, with figures like Galileo, Hooke, and eventually the Bernoulli brothers contributing to its theoretical foundation. The famous challenge issued by Johann Bernoulli in 1696—the brachistochrone problem—ultimately led to deeper investigations of curves including the catenary. It was Christiaan Huygens who first used the term "catenaria" in a letter to Leibniz in 1690, and the mathematical properties were further developed by David Gregory in his 1697 work Catenaria. These developments gradually filtered into architectural practice, allowing for more deliberate and precise application of catenary principles.

Modern computational design has revolutionized the implementation of catenary curves in staircase architecture. Parametric modeling software enables designers to input specific constraints—ceiling height, available floor space, desired tread dimensions—and generate optimal catenary forms that meet these requirements while maintaining structural efficiency. This digital approach allows for experimentation with variations that would have been prohibitively time-consuming to calculate manually. Architects can now visualize how subtle changes to the mathematical parameters affect the final form, enabling truly customized solutions for each unique architectural context.

The aesthetic implications of catenary-based design extend beyond mere structural efficiency. There is an inherent beauty to the catenary curve that humans seem to recognize intuitively—a graceful, natural form that echoes curves found throughout the natural world, from the drape of vines to the arch of a gateway. When embodied in a spiral staircase, this curve creates a visual rhythm that guides the eye upward while suggesting motion and fluidity. The psychological impact is significant: catenary-based staircases often feel more inviting and organic than those based on simpler geometric curves like circular arcs or straight lines.

Material considerations play a crucial role in the realization of catenary-inspired staircases. Traditional stone construction demanded massive central columns to support the cantilevered steps, resulting in dramatic, monumental staircases that dominated their architectural spaces. The development of iron and steel construction allowed for more slender central supports, enabling designers to create staircases that appear to float effortlessly while still following catenary principles. Contemporary materials like reinforced concrete and structural glass have pushed these possibilities even further, creating staircases that seem to defy gravity while actually working in perfect harmony with it.

The relationship between the catenary curve and double-curvature surfaces represents another fascinating dimension of this geometric exploration. Some of the most innovative contemporary staircases employ minimal surfaces—complex three-dimensional forms that extend the catenary principle into sophisticated spatial configurations. These designs often emerge from advanced computational processes that would have been unimaginable to earlier generations of architects, yet they remain fundamentally rooted in the same mathematical principles that governed medieval staircase construction. The continuity of mathematical truth across centuries of architectural innovation presents a powerful testament to the enduring relevance of fundamental geometric principles.

Educational implications of this intersection between mathematics and architecture are profound. The visualization of catenary equations through physical structures like spiral staircases provides a tangible bridge between abstract mathematical concepts and their practical applications. Students of architecture who might struggle with the purely theoretical aspects of calculus or parametric equations often find their understanding transformed when they see these principles embodied in physical structures they can walk on and touch. This embodied learning experience demonstrates the power of integrating mathematical education with practical, visual examples.

Looking toward the future, the integration of catenary principles in staircase design continues to evolve with emerging technologies. 3D printing now enables the creation of complex catenary forms that would be difficult or impossible to produce using traditional manufacturing techniques. Augmented reality tools allow designers to visualize catenary-based staircases in situ before construction begins. And advances in material science promise ever more slender and dramatic implementations of these ancient mathematical principles. Despite these technological advances, the fundamental elegance of the catenary curve remains unchanged—a timeless mathematical truth that continues to inspire architectural innovation.

The geometry of spiral staircases and the visualization of catenary equations represent more than just a technical achievement—they embody the enduring dialogue between mathematics and art, between calculation and creativity. These staircases stand as physical manifestations of mathematical elegance, reminding us that the most practical solutions often emerge from the most abstract principles. As we continue to push the boundaries of architectural design, the humble catenary curve remains a testament to the power of mathematical thinking to create structures that are not only stable and efficient, but truly beautiful.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025